Deep Dive: The yETH Weighted StableSwap Exploit - Part 1

An in-depth analysis of the yETH Weighted StableSwap exploit, exploring how the transition from Curve's invariant to a weighted model introduced critical vulnerabilities through product-term collapse.

Nolan Wang

Founder @ExVul

yETH's Weighted StableSwap is essentially an "evolution story": it moves from Curve Finance's assumption of strict equality to a more flexible, managed pool composition. To understand yETH, we need to start from its predecessor.

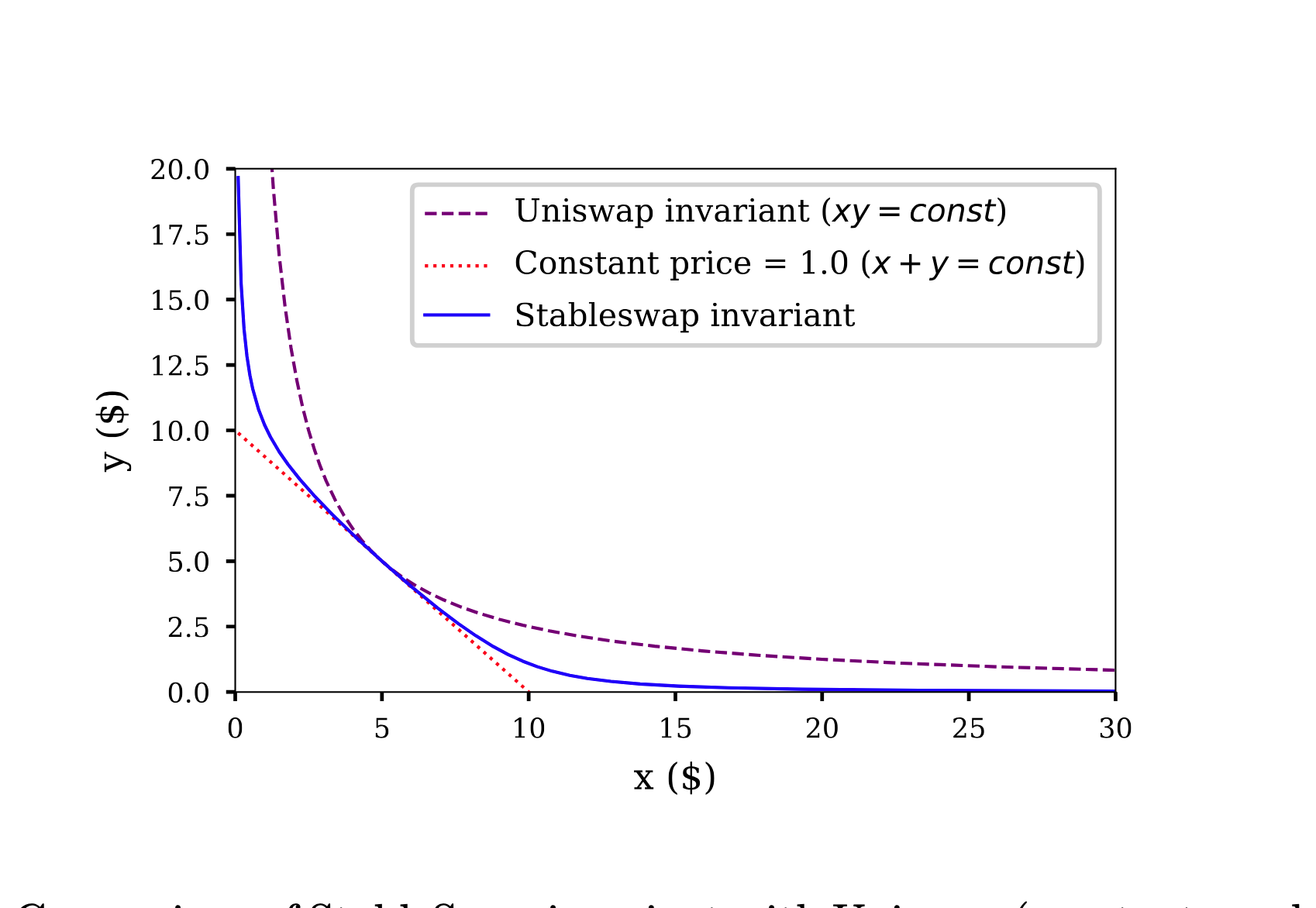

From Curve to yETH: The Evolution of StableSwap

Curve's original StableSwap invariant revolutionized DeFi—it is a clever piece of math designed specifically for stablecoins like USDC and DAI. Curve's brilliance lies in its simplicity: it assumes the assets in the pool are fundamentally equivalent, and the ideal state is to hold them in a perfect 1:1 ratio. By mathematically enforcing this balance, as long as the pool stays reasonably close to equilibrium, traders can swap large amounts of stablecoins with extremely low slippage.

Yearn faced a very different challenge with yETH. yETH is not a basket of identical stablecoins; it is an index of Liquid Staking Tokens (LSTs) like stETH and rETH. While these tokens all track the price of ETH, they are not identical—risk profiles, yield sources, and decentralization differ. Yearn didn't want a pool that blindly holds equal amounts of each LST. They needed a way to express preferences—for example, holding more of a battle-tested LST and less of a newer one—while still preserving the low-slippage benefits that made Curve so successful.

This is what gave birth to Weighted StableSwap. Instead of requiring balance when "asset quantities are equal," it requires balance when "asset quantities match the target weights." The mechanism is "Virtual Balances": the math normalizes real balances by weights so that the underlying StableSwap engine can treat these weighted amounts as if they were equal.

So you can think of Curve StableSwap as the perfect engine for "equal siblings" (stablecoins), while yETH's Weighted StableSwap is a custom engine for a "managed team" of assets: it retains deep liquidity and price stability, but adds a programmable control layer so the protocol can explicitly specify the ideal pool composition.

This is the (classic) Curve StableSwap invariant:

- 𝑛: number of tokens in the pool

- 𝑥𝑖: the balance of token 𝑖 (after scaling)

- 𝐴: amplification parameter

- 𝐷: the invariant / "virtual total liquidity" variable

- ∑𝑖𝑥𝑖: sum of all token balances

The standard form is:

yETH's Weighted StableSwap invariant:

yETH Exploit Analysis

The attacker pushes yETH's Weighted StableSwap into an extreme numerical regime: first compress one asset's virtual balance to be very small; then craft an add_liquidity that makes the product term in the invariant extremely small; finally, inside _calc_supply(), the product term (r) collapses to 0 due to repeated integer floor-division updates. Once r = 0, the iteration for the supply invariant 𝐷 loses a key constraint, so the computed 𝐷 becomes significantly inflated; this bad state can also be written back into packed_pool_vb, creating the conditions for later extraction.

To align with the whitepaper notation, the mapping between symbols and contract variables is: 𝐷 corresponds to vb_sum; the product term ∏ corresponds to vb_prod / vb_prod_final; the supply 𝑠 corresponds to supply (in _calc_supply, s/sp represent the iterates 𝑠/𝑠′). The exponent 𝑤𝑛 corresponds to wn in the contract.

Phase 1: Setting up "product-term collapse (r→0)"

Phase 1 can be summarized as: (1) make the virtual-balance distribution extremely imbalanced; (2) push vb_prod/vb_prod_final low enough so that, inside _calc_supply(), r becomes 0 after repeated floor-division updates.

First, the attacker "shapes" the asset distribution by looping add_liquidity and remove_liquidity(all). Because yETH has 8 assets and remove_liquidity reduces all assets pro-rata by LP share, the attacker can repeatedly do "touch only some assets, then pro-rata remove across all assets," gradually compressing one asset's vb to an extremely small value.

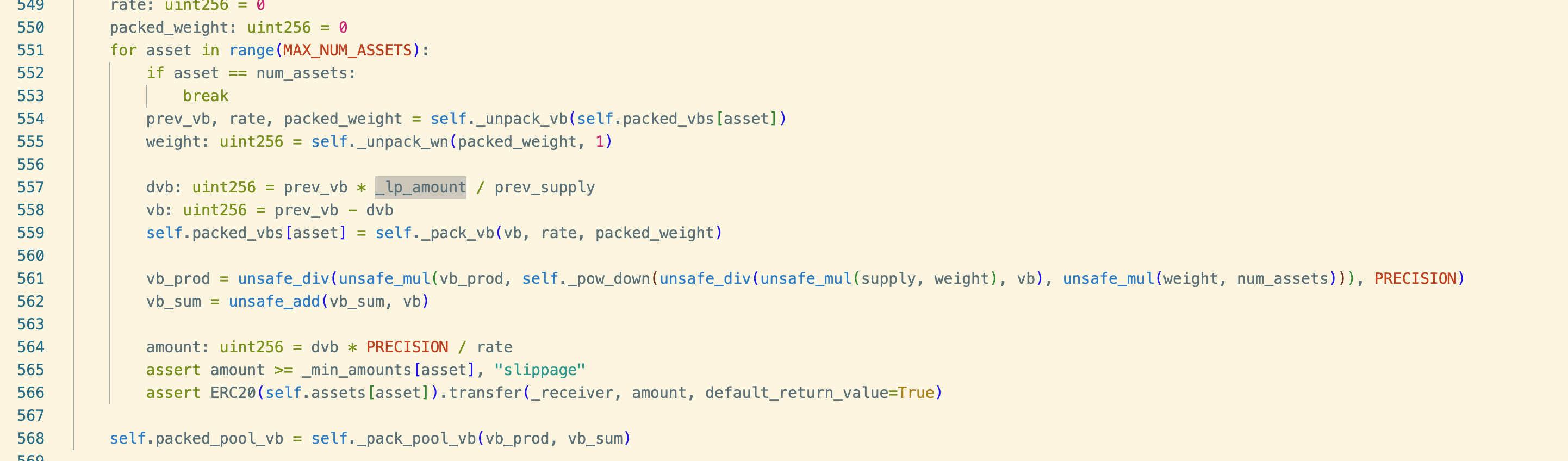

During remove_liquidity, the contract reduces each asset's virtual balance pro-rata based on prev_vb. This is not a vulnerability by itself, but it provides the attacker a controllable process to slowly push one asset's vb toward an extreme minimum.

This is the setup. Initially, the pool's virtual balances are normal:

Initial virtual balances: vb[0]: 732238670963976950498 vb[1]: 439005972161549397592 vb[2]: 218557428174209563351 vb[3]: 311721729094480643686 vb[4]: 235291963478021458031 vb[5]: 878774595504189534046 vb[6]: 57870521296717150423 vb[7]: 55571431079330839150Update vb_prod, supply routine:

add_liquidity(0,1,2,4,5) <——-----↑↓ \ \ ↑↓ \ ->calc_supply---------->\ -↑----->(update vb_prod, D) ↓ ↑↓->remove_liquidity(all)->->->->->After four rounds, the distribution becomes extremely skewed: vb[3] (Asset 3) is compressed to ~1.1% of its original value (3532430177171936798 / 311721729094480643686), while other assets remain large:

vb[0]: 684908434204245837382 vb[1]: 684906035678011109882 vb[2]: 410441629717699458558 vb[3]: 3532430177171936798 vb[4]: 410441628495198523353 vb[5]: 549134391241242137316 vb[6]: 655788662506859028 vb[7]: 629735375533480721After the fourth remove_liquidity, rate/weight still look "normal," but the tiny vb[3] has already planted the seed for product-term instability.

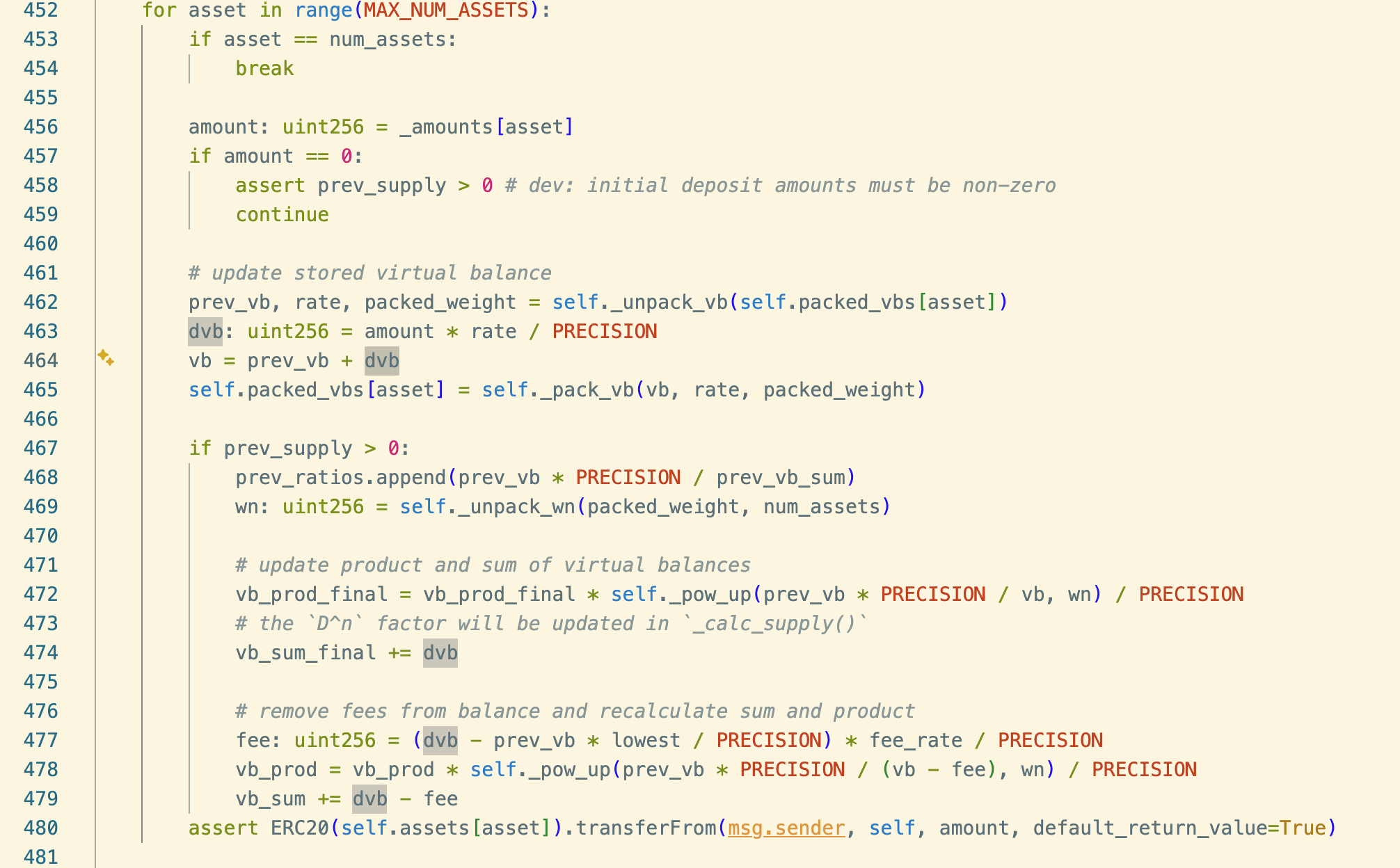

Next, the attacker crafts a key add_liquidity. In the contract, the real amounts are converted into virtual-balance deltas using each asset's rate:

# update stored virtual balance prev_vb, rate, packed_weight = self._unpack_vb(self.packed_vbs[asset]) dvb: uint256 = amount * rate / PRECISION vb = prev_vb + dvbAssets to deposit in the 5th add:

function _getPhase6Add1Amounts() internal pure returns (uint256[8] memory amounts) { amounts[0] = 1_784_169_320_136_805_803_209; amounts[1] = 1_669_558_029_141_448_703_194; amounts[2] = 1_135_991_585_797_559_066_395; amounts[4] = 1_061_079_136_814_511_050_837; amounts[5] = 1_488_254_960_317_842_892_500; }After the fifth add, multiple assets' vb jump significantly, while Asset 3 remains tiny:

=== After fifth add === Asset 0 VB: 2722795789717095953933 Rate: 1142205132950380419 Weight: 200000 Asset 1 VB: 2722786259230849981416 Rate: 1220610597524900457 Weight: 200000 ... Asset 3 VB: 3532430177171936798 Rate: 1117012593717150179 Weight: 100000 ...Now comes the part that actually makes the product term small. When prev_supply > 0, add_liquidity updates the product term using a "ratio-to-a-power." This matches the whitepaper: when an asset goes from 𝑥_old to 𝑥_new, the product term is multiplied by (𝑥_old/𝑥_new)^𝑣𝑖. In the implementation, it uses the "effective balance," i.e., net of imbalance fees:

for asset in range(MAX_NUM_ASSETS): if asset == num_assets: break amount: uint256 = _amounts[asset] if amount == 0: assert prev_supply > 0 # dev: initial deposit amounts must be non-zero continue # update stored virtual balance prev_vb, rate, packed_weight = self._unpack_vb(self.packed_vbs[asset]) dvb: uint256 = amount * rate / PRECISION vb = prev_vb + dvb self.packed_vbs[asset] = self._pack_vb(vb, rate, packed_weight) if prev_supply > 0: ... # remove fees from balance and recalculate sum and product fee: uint256 = (dvb - prev_vb * lowest / PRECISION) * fee_rate / PRECISION vb_prod = vb_prod * self._pow_up(prev_vb * PRECISION / (vb - fee), wn) / PRECISION //-------->(2) ...Because this add makes 𝑥_new much larger than 𝑥_old for several assets, we have 𝑥_old/𝑥_new ≪ 1. Raising this "less-than-1 ratio" to 𝑣𝑖 and multiplying across assets causes the product term to decay rapidly. You can compute this with calculate_vb_prod.py; one result is vb_prod = 3527551366992573 (about 0.0035 in 18-decimal precision), which reflects this decay.

There's a subtle but critical detail: vb_prod_final is updated using prev_vb / vb, while vb_prod is updated using prev_vb / (vb - fee). Since vb - fee < vb, in the "ratio < 1" regime we get prev_vb/vb < prev_vb/(vb-fee), so vb_prod_final decays more aggressively and is usually smaller than vb_prod. This matters because the value ultimately written into packed_pool_vb is vb_prod_final.

The fatal step in Phase 1: floor-updating r in _calc_supply() drives r→0

When the product term is already very small, the contract enters _calc_supply() and uses Newton iteration to solve for the new 𝐷. The key fragment in the contract implementation is:

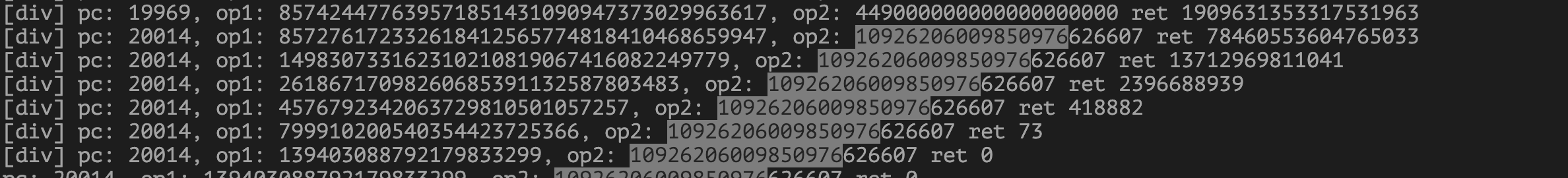

def _calc_supply( _num_assets: uint256, _supply: uint256, _amplification: uint256, _vb_prod: uint256, _vb_sum: uint256, _up: bool) -> (uint256, uint256): ... for _ in range(255): ... sp: uint256 = unsafe_div(unsafe_sub(l, unsafe_mul(s, r)), d) # D[m+1] = (l - s * r) / d for i in range(MAX_NUM_ASSETS): if i == _num_assets: break r = unsafe_div(unsafe_mul(r, sp), s) # r * sp / s //---------> r will turn into 0 ...The update of r looks like r = r * sp / s, but it runs _num_assets times, so the overall effect is approximately 𝑟_new ≈ 𝑟_old * (𝑠'/𝑠)^𝑁.

The real problem is that the division is unsafe_div (integer floor division). When r is already tiny and some iteration steps have sp < s (i.e., 𝑠' < 𝑠), repeated floor(r * sp / s) quickly erodes r. Once an update hits r * sp < s, that step becomes r = 0, and in subsequent iterations r remains 0.

From dynamic analysis, we can see that after about 6 Newton iterations, unsafe_div(unsafe_mul(r, sp), s) drives r to 0, which is exactly this mechanism.

In the sixth interation: r*sp= 139403088792179833299,s=10926206009850976626607(r*sp/s)==0When r = 0, the supply update degenerates to:

The corresponding code in functionn _calc_supply is:

sp: uint256 = unsafe_div(unsafe_sub(l, unsafe_mul(s, r)), d)=> sp: uint256 = unsafe_div(r, d)Clearly the denominator's value changes (the ∏ constraint on 𝐷 is completely removed). Under normal conditions, ∏ exerts a strong corrective force on 𝐷 when the pool is extremely imbalanced, preventing the system from overestimating supply using only ∑ (the sum of balances). Once that constraint disappears, the 𝐷 iteration decouples from the true imbalance and becomes significantly inflated (consistent with your observation that "D is amplified and far above the real value").

In the latter half of add_liquidity (protocol fee minting / final pool-state update), the contract runs _calc_supply(...) again using vb_prod_final and vb_sum_final, and writes the returned vb_prod_final and vb_sum_final into self.packed_pool_vb. If this iteration also experiences the r→0 collapse, the pool can end up storing an abnormal vb_prod_final == 0 state.

# mint LP tokens... supply_final, vb_prod_final = self._calc_supply(num_assets, prev_supply, self.amplification, vb_prod_final, vb_sum_final, True)... self.packed_pool_vb = self._pack_pool_vb(vb_prod_final, vb_sum_final)At this point, the initial key step of the attack is complete: vb_prod becomes 0 and 𝐷 is inflated. The attacker then exploits the inflated 𝐷 to mint excess liquidity and ultimately drain the pool; we will cover this process in detail in Part 2.

Note: the exploit PoC in this write-up is based on DeFiHackLabs yETH_exp.sol.

About ExVul Security

ExVul is a Web3 security company focused on building a safer ecosystem with end users and vendors. We provide smart contract audits, protocol audits, wallet audits, security consulting, and Web3 penetration testing. Our team members come from Huawei, 360, Amber, ByteDance, Movebit, and PeckShield, including top-tier global white-hat hackers.

Partners include OKX, Bitget, Stacks, Yala, Axelar, Cobo, UxLink, Pharos, Aptos, Sui, CoreDAO, Mango, Immunefi, HackenProof, and File Swan Cloud.

Website: https://exvul.com

X: https://x.com/exvulsec

References

- Yearn Security Disclosure (2025-12-01)

- Curve StableSwap Whitepaper

- DeFiHackLabs PoC (yETH_exp.sol)

- https://github.com/exvulsec/yETH-Exploit-analysis/blob/main/calculate_vb_prod.py